If you want to know more information (such as product/process price, etc.), please contact us 24-hour telephone

Alluvial gold, often called placer gold, is gold that’s been freed from its original rock through years of natural erosion. It ends up as tiny flakes, grains, or nuggets mixed with sand, gravel, or clay in places like riverbeds, floodplains, or old stream channels. These spots form when gravity pulls heavier gold particles down during sediment movement, leaving them in areas where water slows down.Unlike hard rock mining, where you blast and grind rock to get gold, alluvial gold is already loose, so it’s cheaper and quicker to process. For instance, an alluvial gold processing plant skips the heavy crushing step, cutting energy use by 30–50%.

You’ll find alluvial gold in places shaped by water over centuries. Riverbeds are a classic spot—gold gets trapped in gravelly patches where the current eases up. Floodplains, where rivers spread sediment during floods, are another hot zone. Coastal beaches, like those in New Zealand, can hold gold washed up by waves. Even ancient, dried-up riverbeds—called terraces—can hide gold, like in Australia’s Victoria region. Each spot’s unique, but the gold’s always free, not stuck in rock, which makes it perfect for simple gravity-based recovery.

Gold’s weight is the star of the show here. With a specific gravity of 19.3, it’s way denser than sand or gravel (around 2.6–2.7). This means gold sinks fast when you swirl it in water, making gravity separation the go-to method. Since it’s already loose in alluvial deposits, you don’t need chemicals—just clever equipment. Particle size matters too. Big nuggets are easy to catch, but fine gold dust needs fancier tools like centrifugal concentrators. Clay can be a pain, gumming up the works, so you’ve got to break it up first. Other heavy minerals, like magnetite, can tag along, but gold’s density makes it stand out. I’ve seen miners in Somalia deal with sticky clay—it’s a hassle, but proper screening saves the day.

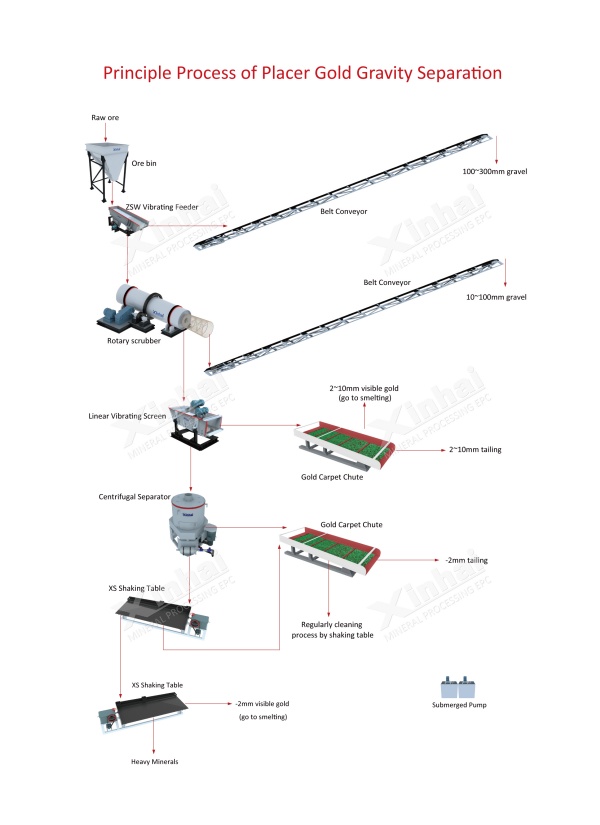

An alluvial gold processing plant is like a well-oiled machine, with each part doing a specific job. First, you’ve got feeding systems—think hoppers or conveyors that dump raw dirt into the plant. Next come washing units, like trommel scrubbers, which clean the material by tumbling it with water. Classification gear sorts it by size, so you’re not wasting time on big rocks. Gravity concentrators, like jigs or centrifugal units, grab the heavier gold. Shaking tables fine-tune the process, catching tiny gold bits. Finally, sluice boxes scoop up any leftover gold from tailings. The whole setup—feeding, washing, sorting, concentrating, and refining—works together to pull gold out efficiently.

The process is straightforward but precise. Raw material goes into a hopper first. From there, it hits a trommel scrubber, where water and tumbling break up dirt and clay. Next, screens sort the mix into different sizes—big chunks go one way, finer stuff another. Gravity separation comes next, using jigs or centrifugal concentrators to grab coarse gold. Shaking tables take over for the fine stuff, concentrating it further. If you want pure gold, smelting might be the final step. It’s a three-part dance: screen, sort, purify. Each step builds on the last, and skipping one can mess up your recovery.

Trommel screens are big, rotating drums with holes that act like giant sieves. They spin, letting small particles pass through while kicking out oversized rocks. This keeps the downstream gear from clogging. For cleaner deposits with no sticky clay, a trommel screen is perfect for washing raw material. Picture a site in Mongolia—miners feed gravelly riverbed dirt into the trommel, and it spits out clean, sorted material ready for the next step.

Jig concentrators are clever. They use pulsing water to make heavy gold settle while lighter stuff floats away. The Xinhai jig, with its tapered slide valve, boosts processing by over 35%. It’s easy to tweak the stroke and frequency, which is great for handling different deposit types. Miners love it for coarse gold—say, nuggets in an Alaskan placer—because it’s simple and effective.

Shaking tables are where the magic happens for tiny gold particles. They vibrate gently, letting gold settle into riffles on a slanted deck. The Xinhai 6s table, for example, runs smoothly, uses less power, and adjusts easily. It’s a game-changer for fine gold recovery, like in Australia where miners deal with flour-like gold dust. The compact design saves space, too.

Spiral Chute are long, sloped channels lined with mats or riffles that trap gold as water washes lighter material away. They’re great for catching tailings—gold that slips through other machines. A gold sluice box often pairs with a centrifugal concentrator to grab every last bit. I’ve seen small-scale miners in Ghana swear by sluices; they’re cheap and catch gold others miss.

Sorting material by size is critical. Multi-stage screening removes big rocks and debris, ensuring only the right-sized stuff hits the concentrators. This prevents clogs and boosts efficiency. For example, in a high-clay deposit in Somalia, miners use extra screens to keep the flow smooth. Without this, you’re just overloading your gear and losing gold.

Water flow and equipment slope need to be just right. Too fast, and you wash away fine gold; too slow, and lighter stuff clogs the system. Miners tweak sluices and tables to find the sweet spot, often testing different angles on-site. In arid regions, like parts of Australia, they recycle water to keep things running without wasting a drop.

Gravity separation is the heart of alluvial gold processing plants. It’s cheap, green, and works because gold’s so heavy. Unlike hard rock mining, which often uses nasty chemicals like cyanide, gravity methods rely on water and motion. Practice shows it’s the most effective and budget-friendly way to process placer gold.

Take Somalia’s 200TPH project. They use a gravity-plus-mercury amalgamation setup. Large gravels are removed first, then coarse gold is recovered via amalgamation. It’s simple, with fast returns—perfect for riverbed mining where gold’s plentiful but mixed with junk.

Hard rock mining is a different beast. It starts with blasting rock, then crushing and grinding it into powder. After that, you might use flotation or cyanidation to extract gold—both energy-hungry and chemical-heavy. An alluvial gold processing plant, though, deals with gold that’s already free. It skips the crushing and grinding, focusing on washing and gravity separation. This cuts costs and environmental impact, making it ideal for smaller operations or remote sites.

| Aspect | Hard Rock Gold (Lode Gold) | Alluvial Gold (Placer Gold) |

|---|---|---|

| Deposit Characteristics | Gold locked within solid rock, often associated with quartz veins and sulfide minerals | Free gold particles found in riverbeds, floodplains, or alluvial sediments |

| Main Mining Methods | Underground mining, open-pit mining, drilling, and blasting | Surface mining, panning, dredging, sluicing, hydraulic mining |

| Comminution | Requires crushing and grinding to liberate gold from ore | Generally no crushing/grinding needed, as gold is already liberated |

| Main Processing Techniques | Gravity separation, flotation, cyanidation (CIP/CIL), smelting | Mainly gravity separation (sluice boxes, jigs, shaking tables, centrifugal concentrators) |

| Chemical Use | Often necessary (cyanide leaching, flotation reagents) | Usually avoided; mostly physical separation without chemicals |

| Plant Complexity | Complex process flowsheet with multiple stages of crushing, grinding, and chemical treatment | Simpler setup with washing, screening, and gravity concentration |

| Capital & Operating Cost | Higher due to drilling, blasting, grinding, and chemical reagents | Lower, since only washing and gravity separation equipment are needed |

| Gold Recovery | Effective recovery of fine and refractory gold possible, but requires advanced technology | High recovery of coarse and fine free gold, but limited for ultrafine particles |

| Environmental Impact | Higher impact due to tailings, chemicals, and energy consumption | Lower impact if mercury and harmful chemicals are avoided |

FAQ

What equipment is used in an alluvial gold processing plant?

A typical setup includes trommel scrubbers for washing, jig separators or centrifugal concentrators for rough separation, shaking tables for final concentration, sluice boxes for tailings recovery, feeding hoppers/conveyors, and sometimes a smelting furnace for onsite refining. For example, a 150tph complete alluvial gold processing plant uses a trommel scrubber, centrifugal concentrator, shaking table, sluice box, and melting furnace.

How much does it cost to set up an alluvial gold plant?

Costs range from $800,000–$2 million for a 100-ton-per-day plant. Modular designs can save up to 30%, making them a smart pick for smaller operations.

What recovery rate can be expected from alluvial processing?

You can expect 85–92% recovery with well-designed gravity-based systems, especially when using centrifugal concentrators for fine gold recovery.